Cruise on over to this celebration of of...

RR Boxcar Communities

Sampler Lecture

Nearly 100 people attended the fourth and final Sampler Series lecture on Monday, April 18, at the McHenry County Historical Society Museum.

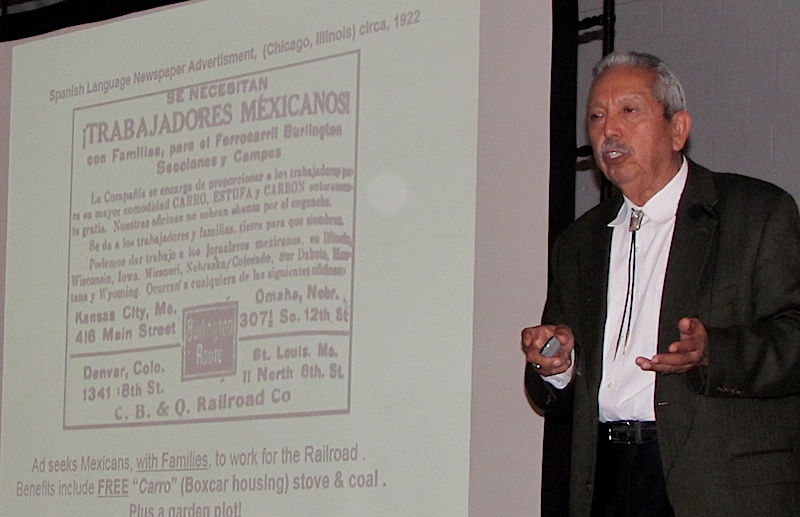

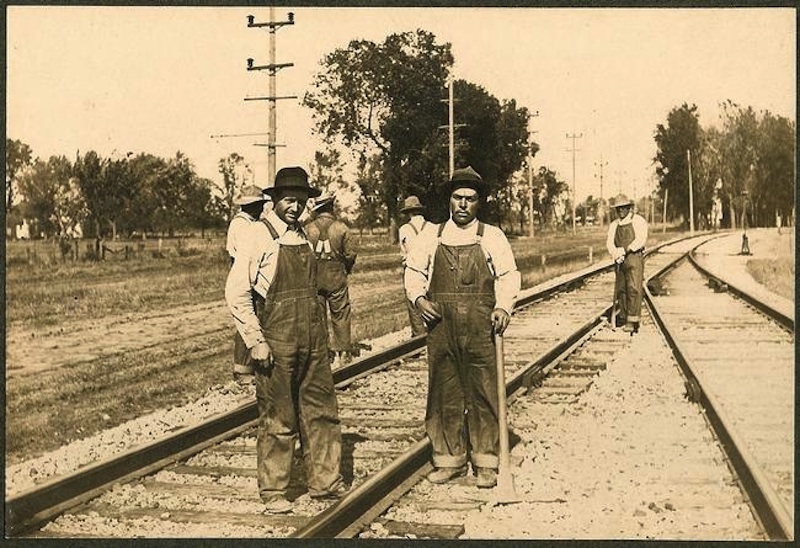

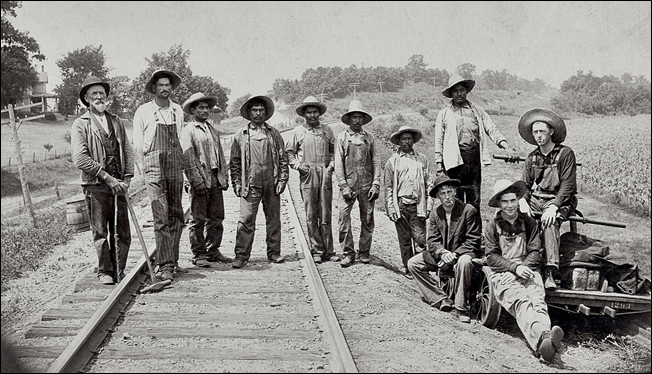

In “The History of the Mexican Railroad Boxcar Communities in Chicago & the Midwest,” speaker Antonio Delgado discussed the reasons behind and the processes used to recruit Mexican railroad workers recruited to the United States during the turn of the century and into the 1950s. They laid track, maintained the rights-of-way and made repairs for the Chicago & North Western, Elgin, Joliet & Eastern, Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy railroads in this area, as well as for lines farther west.

In 1927-28, there were 20 railroad camps sprinkled across Illinois, housing between 75 and 200 people in each camp. They ranged from Pekin to LaFox; even a small one in Hebron. None featured plumbing, hot water or much privacy. Curtains were used to cordon off rooms in the roughly 300-square-foot wooden boxcars that were 8-foot-6-inches wide and 36 feet long. It was not unsual for families of eight to 10 people, often four generations, to live in two of these boxcars.

"Collectively, they worked like 120 years [in this country]. You can't get more American than that," Delgado said.

Others made crude houses out of creosote-soaked railroad ties and still others – fortunate and favored enough – were able to live in modern "section" housing or bunkhouses that featured amenties such as common kitchens and flush toilets. But the latter was the exception.

"This is not This Old House we're looking at," Delgado said. "They were all homemade. There was no standard."

If siding, gardens, porches or cement block foundations were added, the workers are the ones that paid for it and did the work.

A 1912 edition of the Railway Age Gazette notes:

“The Mexican is an interesting type of track laborer, and one with whom the average roadmaster or supervisor is unfamiliar. Five years ago his activities in this country were confined to a limited area in the southwest adjacent to El Paso and the Mexican border. Within the past three or four years Mexicans have been in such demand and have come into this country in such numbers that they are now the main source of supply for the roads west and south of Kansas City and are found in large numbers in Missouri, Iowa and Illinois.”

The number of these railroad track workers, or “traqueros,” ballooned following the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law implemented to prevent a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the United States. Many came from the central plateau of Mexico, from the states of Michoacán, Jalisco and Guanajuato.

“The Mexican possesses a number of characteristics which tend to make him a good track man, comparing him with other track men as we find them today,” wrote the Railway Age Gazette. “He often prefers section work to extra gang work, because he wishes to bring his family with him … He is peaceable and quiet about the camp and causes little complaint from neighboring residents. The Mexican is very loyal to the foreman who commands his respect. This was shown by the way the Mexican gangs worked during the unusually severe snow blockades on the Santa Fe and other western lines last winter. Although unaccustomed to cold and snow, they labored more faithfully than many native gangs in opening the lines, frequently remaining on duty more than 24 consecutive hours in extremely severe weather.”

The demand for cheap, productive labor accelerated the need for housing. Boxcars filled the bill – replacing tent camps – with mobile homes that could be moved by rail and put on a siding for weeks or months until it was time to relocate.

Recruitment ads touted free boxcar housing, a stove and coalSimple holes were cut for windows. Wood stoves provided heat. But as family members joined workers and and foremen got to know them, Mexicans began to add porches, gardens and other more personalized touches including places of worship.

“It’s a work in progress,” Delgado said of his seven-year journey to learn more about this multi-generational piece of our past. “My job is to put it in accurate, historical context.”

Immigrant railroad workers and their families lived on railroad property, often less than 20 feet from the tracks – a very dangerous proposition according Jeffrey Marcos Garcílazo, author of “Traqueros: Mexican Railroad Workers in the United States, 1870-1930.”

“The centrality of the boxcar community to Mexican immigrant life in the United States is due largely to its proximity to the railroad yards. But the convenience of proximity and free rent took a terrible toll on the inhabitants,” Garcílazo wrote. “Accidents were a common occurrence.”

But despite the danger of being run over or struck by trains, the boxcar communities thrived. One was located on the south side of Galesburg, another in West Chicago and yet another near Aurora that boasted 1,000 people by the late ’20s. Mexican workers recycled parts from railroad cars and engines at a CB&Q plant in Eola until the facility closed in 1934.

At that point, many of the Mexican inhabitants dissembled the cars and used the lumber to build permanent homes in the area.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.