Cruise on over to this celebration of of...

Historic Sears faces a bumpy road ahead

A surprising headline caught my eye just before Memorial Day: Sears Holding Corp. reported its first quarterly profit in nearly two years.

My enthusiasm was tempered by the fact that sales at American Sears’ stores open for more than a year fell 12.4 percent, and Kmart (remember that?) sales in the U.S. fell nearly as much. Still, net income for Sears’ shareholders was $244 million, or $2.28 a share, compared with a loss of $471 million last year, or $4.41 a share.

So is the $1.25 billion cost-cutting plan finally paying off? Perhaps in the short term, but it is hard to believe that further reducing its footprint will lead to sustained growth. The decision this year to close 180 underperforming Sears stores and consolidating the corporate operations of Sears and Kmart are among a a litany of decisions that have financial analysts and the public alike scratching their heads.

That list includes John Arganbright, a native of Columbus, Ohio, who now calls Sun City Huntley home.

“The chances of survival are thin,” he said. “They won’t survive as the Sears we grew up with, I guarantee you.”

Arganbright worked a little more than 30 years for Sears in the U.S. and another couple of years at Sears in Canada in sales, purchasing, marketing, merchandising and training – both in the field and at headquarters. From 1 to 2:30 p.m. Aug. 2, he will share that insight during “Sears Roebuck: The Rise and Fall of a True American Icon” for McHenry County College’s Retired Adult Program. For information, visit www.mchenry.edu/rap or call 815-455-8559.

There were and are executives in the company with more “connections,” but it is hard to imagine many people with a broader sense of how Sears functions – or rather, should function.

“We had money everywhere. … We literally didn’t know what to do with it,” Arganbright said. “Sears made more short-term loans than any other bank, but we did too much short-term lending for long-term capital improvements.”

Sears also failed to adapt quickly to a changing environment.

“We were real estate heavy, and we owned a lot of stores – something like 65 to 75 percent,” Arganbright said. “Typically, a store was over 100,000 square feet, and a lot of prime real estate was in malls. Unfortunately, malls were not the wave of the future. People don’t go to the malls.”

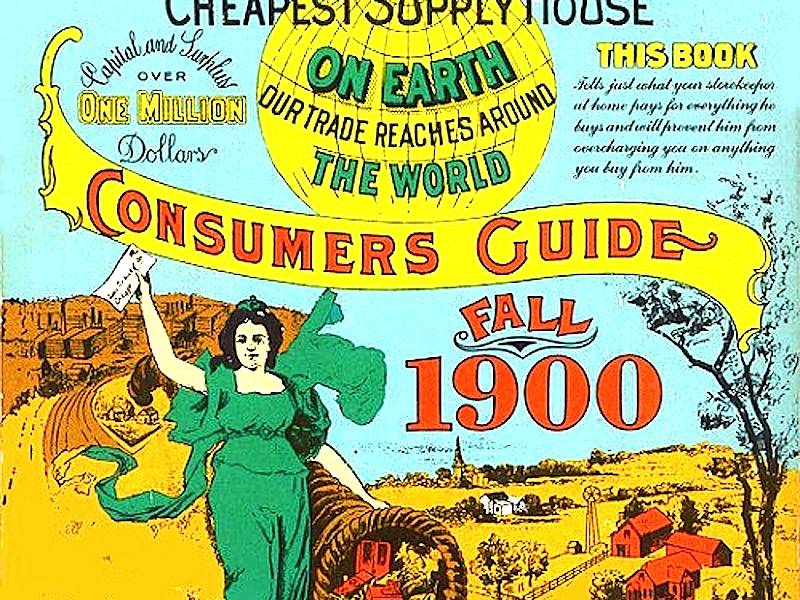

In 1886, Richard Sears started selling watches to supplement his income as station agent at North Redwood, Minnesota. After relocating to Chicago in 1887, he hired Alvah C. Roebuck to repair watches and established a mail-order business for watches and jewelry. A catalog, first just for watches and jewelry, arrived in 1895. It later included all manner of things – ranging from chickens to houses, potions to automobiles, tombstones to textiles – that could be delivered to the remotest corners of the country. It was an early Amazon.

“Everybody had somebody who worked at Sears or knew somebody who worked at Sears,” Arganbright said. “It was a one-stop shop and a powerhouse in the late ’60s.”

But even before Sears discontinued its “Big Book” catalog in 1993, the retailer was experiencing hard times.

“We brought somebody in (Arthur C. Martinez, 1995) who didn’t know about merchandising. … We brought in lawyers to run the company,” Arganbright said. “We tried to buy freight lines and banks. What we didn’t have was a strategy for doing something internally in the stores.”

Arganbright said paint – Easy Living and Weatherbeater – was the first casualty. Licensing agreements for DieHard and Craftsman followed.

“They have been trying to sell the brands for 20 years with different types of licensing agreements,” he said. “That is when I knew we were in trouble.”

Furthermore, that lack of exclusivity undermined the relationships Sears had built with manufacturers – including Schwinn bikes and Whirlpool.

“We were the powerhouses, and they did everything we asked them to do. As we became less powerful, we lost leverage,” Arganbright said. “When you start screwing around with those relationships, customers see it – sooner or later.”

Arganbright believes that Sears Chairman and CEO Edward Lampert, whose hedge fund owns about 56 percent of the company, would like to downsize to between 200 and 250 stores and increase the company’s online presence. But is it too late?

Arganbright is not optimistic.

“I don’t think it can happen, but I’m hoping Sears succeeds,” he said. “They have to get to size they can afford, and they have to stop the bleeding and rebuild loyalty. … The internal turnover is a problem. The world doesn’t work well with continually brand-new people.”

However, opportunities remain for brick-and-mortar retailers.

“There is no way my wife wants to bring eight dresses home and try them all on,” Arganbright said. “She’s just not going to do that.”

• • •

The McHenry County Historical Society’s 1860 “base ball” club, the “Independants,” will host the Lake County Athletics as part of a home-and-home series at Prairie Grove Village Hall Park, 3125 Barreville Road, Crystal Lake. The game begins at 2 p.m. Sunday. Admission is free.

• Kurt Begalka, former administrator of the McHenry County Historical Society & Museum.

Published June 5, 2017, in the Northwest Herald

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.