Cruise on over to this celebration of of...

Food pantry garden recalls Victory Gardens

Part of our past is taking root in Lake in the Hills.

Laurie Selpien, a Carpentersville native, a 13-year resident of Lake in the Hills and a member of the McHenry County Historic Preservation Commission, launched the idea of re-creating a World War I-era garden at the Algonquin Lake in the Hills Interfaith Food Pantry last year. With assistance from Jacobs High School’s environmental club, the Green Eagles, it is soaring to new heights.

Four hundred families a year benefit from the vegetables grown in between and behind a village-owned horse stable and public works garage at 1113 Pyott Road in Lake in the Hills.

“Last year, we grew just under 4,000 pounds of food – 3,000 at the food pantry and 1,000 pounds of food at the water treatment plant in Algonquin,” Selpien said.

But there has been a learning curve.

“I started out with a Victory Garden theme. Then I found out that I had to teach people what food was first,” Selpien said. “If it didn’t have directions on the side of the box, they didn’t know how to cook it.”

Selpien, a self-taught organic gardener, incorporates a sustainable approach when directing volunteers and working with pantry clients. That meant relying on “companion planting” rather than insecticides to discourage pests and – in a donated greenhouse – a “double watering” system that allows plants to wick up only the moisture they need.

Because Selpien prefers not to work in mud, she opted for 15 raised beds framed with cedar planks to avoid too much runoff from the parking lot and from the buildings that abut it on either side.

“My first goal is to feed people,” Selpien said. “But I also have a lot of heritage seeds, seeds that are disappearing that you can’t find anymore. We have green beans that originally came across [the ocean] on the Mayflower and a green bean they found on the Lewis and Clark expedition.”

Selpien said heirloom varieties, which she insists taste better and pack more nutritional value, are disappearing at a precipitous rate. The nearly 500 varieties of lettuce available in 1903 have been whittled down to 36.

“As far as disease resistance, we’re playing with fire,” she said. "During the last 20 years, the nutritional value of our food has dropped 40 percent.”

She produces a bevvy of statistics to back up the benefit of home-grown produce. On average, the produce you buy at a typical grocery store has traveled nearly 1,500 miles. No wonder Mother Earth News reported that of the 36 million gardening households, more than half reported growing their food because it tastes better and saves them money on groceries. And tomatoes were far and away the most popular crop.

“People are able to taste food the way it is really supposed to taste,” Selpien said.

The 19-acre site that houses the pantry also includes an orchard and three times the garden space compared with last year. The selection includes pretty much every vegetable someone could imagine, plus a few they wouldn’t. The Trail of Tears bean from Seed Savers Exchange, for example, was carried by the Cherokee Indians during their infamous death march to Oklahoma in 1838.

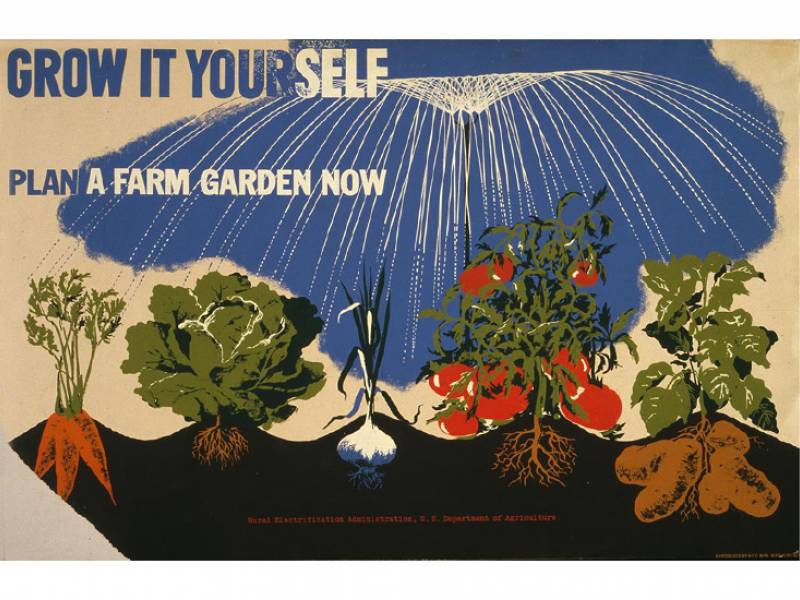

During the first and second world wars, families were encouraged to do their patriotic duty and help themselves eat better by growing their own vegetable gardens. Illinois Superintendent of Schools Vernon Nekell urged his colleagues to establish Victory Gardens on school grounds and educate students to do likewise at home. The program extended into home economics classes, where girls learned how to can fruit and vegetables. In 1917, an estimated half a million quarts of canned fruits and vegetables were produced. The next year, that figure jumped to 1.45 million quarts.

During World War II, an estimated 20 million people followed the example of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who grew her own vegetable garden on the White House lawn. By 1943, these “war gardens” were producing 8 million tons of food – about 40 percent of all the vegetables Americans were eating. Fred B. Morgan, Victory Garden chairman in McHenry County, worked to secure land for community gardens. Hundreds of lots were made available by J.J. Wallace at no charge in country club additions on the south shore of Crystal Lake. The Chicago & North Western Railroad also donated several acres.

“Victory gardening is everywhere in evidence,” the Crystal Lake Herald reported in May 1943. “Many persons now have potatoes, peas, onions and other crops planted. On weekends and evenings it is common sight to see just about everyone working in their garden.”

The homegrown food effort also had the added effect of boosting morale, coincidentally something that is occurring today in Lake in the Hills, as well as in Harvard.

"We’re taking public land and turning it into food. That is exactly what I’m going for,” Selpien said. “People are trying food that they would have never tried before. I had a woman who actually got excited about zucchini.”

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 MCHS- All Rights Reserved.